- Why is vitamin D critically important for the body?

- Metabolic functions and systemic effects

- The winter deficit and its causes

- Dietary restrictions and absorption factors

- Specialized solutions for winter shortages

- Symptoms and health consequences of deficiency

- Musculoskeletal disorders

- Immunological and neurological implications

- Effective prevention and correction strategies

- Pharmacokinetic features and optimization

- Monitoring and laboratory assessment

Why is vitamin D critically important for the body?

Vitamin D functions as a prohormone in the human body, regulating over 1000 different genes and participating in numerous biochemical processes. This fat-soluble vitamin exists in two main forms - ergocalciferol (D2) and cholecalciferol (D3), the latter demonstrating significantly higher bioactivity.

Calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D, acts as a steroid hormone through specialized receptors (VDRs) located in the nuclei of cells. This molecular interaction initiates a cascade of genetic changes that affect calcium homeostasis, immune function, and cell proliferation.

Metabolic functions and systemic effects

In addition to its classical role in calcium-phosphorus metabolism, vitamin D modulates insulin sensitivity, neurological functions, and cardiovascular hemodynamics. Its deficiency correlates with an increased risk of autoimmune diseases, metabolic syndrome, and neuropsychiatric disorders.

The winter deficit and its causes

During the winter months in Bulgaria, solar radiation decreases dramatically, with UV-B rays, necessary for the skin photosynthesis of vitamin D, being practically absent between October and March. The geographical position of the country (42°N-44°N) causes a seasonal deficiency of effective irradiation.

According to research by the European Food Safety Authority, over 80% of the Bulgarian population demonstrates suboptimal serum levels of 25(OH)D during the winter period.

The cutaneous biosynthesis of the precursor 7-dehydrocholesterol is inhibited at solar angles below 50 degrees. Additionally, melanin pigmentation, stratum corneum thickness, and age-related changes in the skin further compromise endogenous production.

Dietary restrictions and absorption factors

Traditional Bulgarian cuisine contains limited amounts of natural sources of vitamin D. Fatty fish, egg yolks, and fortified dairy products provide insignificant amounts compared to physiological needs.

Enteric absorption of vitamin D requires adequate bile salts and lipids. Gastrointestinal diseases such as celiac disease, Crohn's disease, or pancreatic insufficiency can seriously compromise absorption.

Specialized solutions for winter shortages

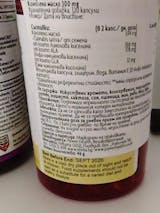

In response to the widespread winter vitamin D deficiency, there are specialized nutritional supplements designed to optimize serum concentrations. The collection of vitamin D supplements offers a variety of formulations adapted to different age groups and physiological needs.

These products include various dosages from 400 IU to 4000 IU, as well as combination formulas with vitamin K2, magnesium and calcium for synergistic action. Liposomal technologies and microencapsulated forms improve bioavailability and ensure stable absorption.

Symptoms and health consequences of deficiency

Vitamin D deficiency manifests a variety of clinical signs, starting from subtle symptoms and progressing to serious pathological conditions. Muscle weakness, chronic fatigue, and osteoarticular pain are some of the early indicators.

Musculoskeletal disorders

- Osteomalacia in adults and rickets in children

- Increased susceptibility to stress fractures

- Myopathy and decreased muscle strength

- Delayed healing of bone injuries

Parathyroid hormone increases compensatorily, leading to secondary hyperparathyroidism. This condition stimulates osteoclast resorption and reduces bone mineral density.

Immunological and neurological implications

Vitamin D receptors on immune cells regulate antimicrobial defense and autoimmune tolerance. Deficiency correlates with increased incidence of respiratory infections, especially during the winter months.

Neurological symptoms include depressive episodes, cognitive impairment, and seasonal affective disorder. Serotonin and dopamine neurotransmission are modulated by adequate vitamin D levels.

Effective prevention and correction strategies

Optimal prevention of winter vitamin D deficiency requires a multifactorial approach combining adequate supplementation, dietary modifications, and physiological exposure planning.

| Age group | Recommended daily dose (IU) | Maximum safe limit (IU) |

|---|---|---|

| 0-12 months | 400 | 1000 |

| 1-18 years | 600 | 3000 |

| 19-70 years old | 800 | 4000 |

| Over 70 years old | 1000 | 4000 |

Pharmacokinetic features and optimization

Vitamin D3 demonstrates significantly higher efficacy compared to the D2 form. Cholecalciferol is hydroxylated in the liver to 25(OH)D3, which serves as the main circulating marker of vitamin status.

Administration with fatty food improves absorption by up to 50%. Concomitant consumption of magnesium and vitamin K2 optimizes metabolic conversion and tissue utilization.

Monitoring and laboratory assessment

Serum 25(OH)D is the gold standard for assessing vitamin D status. Optimal concentrations range between 30-50 ng/ml (75-125 nmol/L), with levels below 20 ng/ml being classified as deficient.

Periodic monitoring during the winter months allows for personalization of therapeutic regimens. High-risk populations include the elderly, immunosuppressed patients, and individuals with limited sun exposure.

Adequate winter vitamin D supplementation is a critical component of a preventive health strategy. A science-based approach to correcting deficiency can significantly improve quality of life and reduce the risk of multiple chronic diseases.